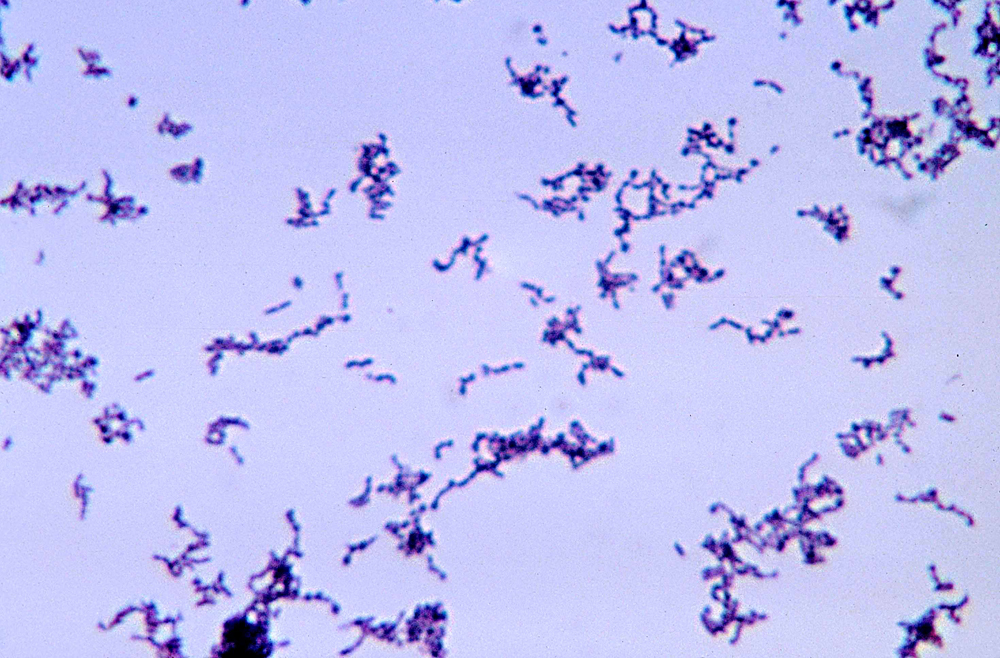

Credit: CDC

If antibiotics are overused, the bugs they cure will build up resistance. This means over time, they’ll become less and less effective until they eventually stop working altogether. That concern has led to much

debate, research, and general conversation inside the medical community about antibiotic stewardship. The idea is that doctors need to be thoughtful about how they prescribe these drugs now to prevent increasing resistance as long as possible.

It’s an idea that’s being explored across the world and in many specialties and subspecialties of medicine. Penn has an entire team dedicated to monitoring the use of antibiotics – part of which was one of the first of its kind in the nation – and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has awarded grants in hopes of generating innovative solutions to the problem. We’ve tackled the issue in this space several times before.

But while discussions on stewardship are often focused on fighting infection among the sickest patients, those aren’t the only people taking these drugs. Data from the CDC shows the average dermatology provider wrote 669 antibiotic prescriptions in 2014, the most recent year for which data are available. That is, by far, the highest average of any provider specialty. For some perspective, the next closest group was primary care physicians, who wrote an average of 483 prescriptions per provider. It begs the question of whether dermatology should be under the microscope when it comes to stewardship.

One reason the numbers might be higher is that dermatologists prescribe antibiotics both as pills and topical medications. While many antibiotics for common infections are prescribed for a period of several days, treatment for dermatological reasons, especially acne, can keep patients on these drugs for months, or even longer.

“If a patient is doing well on oral antibiotics for acne, you tend to not want to stop it,” said David J. Margolis, MD, PhD, a professor of Dermatology. “It’s not curative, so you get into this conundrum of what you’re supposed to do as a clinician to keep someone in good shape.”

The statistics prove his point. A recent New York University study found the average patient who is on oral antibiotics for acne will stay on the medication for 331 days, essentially a full year.

“Current guidelines claim we should limit use of oral antibiotics to six months,” Margolis said. “But statistically, the rate of prescribing antibiotics among dermatologists hasn’t changed all that much over the years.”

Margolis also points out a key difference between the patients who take these drugs for acne as opposed to other infections.

“Acne patients are relatively healthy people who are on antibiotics for weeks or months, as opposed to people who are sick and are on these drugs for a week,” Margolis said. “Yet infectious diseases doctors, from the time of prescription, are worried about how long a patient is going to be on antibiotics. Dermatologists don’t.”

All of this is before we even dive into the issue of topical antibiotics. Recent research from the laboratory of Elizabeth Grice, PhD, an assistant professor of Dermatology, shows topical antibiotics can have long term effects on the communities of bacteria that live on the skin, potentially opening the door for colonization by an unwanted strain.

It’s not as if these antibiotics only treat acne. These same drugs can also be used to treat community-acquired MRSA, Lyme disease, sexually transmitted diseases, and urinary tract infections. The stakes for resistance to these treatments are real. Even acne itself will become resistant over time.

Despite all of this data, dermatology remains in the background of the conversation on antibiotic stewardship. Ebbing Lautenbach, MD, MPH, MSCE, chief of Infectious Diseases, has a theory on why.

“A major focus of antibiotic stewardship is on areas where antibiotics aren’t called for, where a doctor might write the prescription without thinking about why and how they’re using it,” Lautenbach said. “That’s not usually the case in dermatology.”

Margolis agrees.

“Most dermatologists are consciously following a step-by-step concept where they try topicals first – maybe more than one – and if that doesn’t work, then they go to oral antibiotics,” he said.

Lautenbach also points out that any doctor prescribing antibiotics should be weighing the pros and cons, and with dermatology, there’s a documented benefit to most of these drugs.

“We need to distinguish between antibiotic use that is inappropriate or too long in duration and situations where a patient stays on a drug because it’s helping them,” he said.

Lautenbach says physician education has been focused on the people who prescribe the most antibiotics. While, as noted above, dermatologists are prescribing more per practice, their total number of prescriptions pale in comparison to outpatient primary care doctors. That same CDC report found dermatologists wrote a total of 7.6 million prescriptions for antibiotics in 2014, while primary care physicians wrote 114.7 million.

“From an education standpoint, there tends to be more value in focusing our efforts on outpatient primary care prescribers,” Lautenbach said. “Dermatology isn’t where we find most use of antibiotics in terms of sheer volume.”

But, Lautenbach and Margolis say, that doesn’t mean dermatologists shouldn’t be part of the conversation.