Penn Medicine takes the Lead in Kinase Inhibitor Therapy for Radioactive Iodine-Refractory Differentiated Thyroid Cancer

For more than a decade, Penn Otorhinolaryngology–Head and Neck Cancer has been home to one of the nation’s leading clinical and research programs for advanced or metastatic radioactive iodine refractory differentiated thyroid cancer. The program has been the catalyst for the development of novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapies for radioactive-iodine refractory thyroid cancer patients who previously had no effective treatment options.

For more than a decade, Penn Otorhinolaryngology–Head and Neck Cancer has been home to one of the nation’s leading clinical and research programs for advanced or metastatic radioactive iodine refractory differentiated thyroid cancer. The program has been the catalyst for the development of novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapies for radioactive-iodine refractory thyroid cancer patients who previously had no effective treatment options.

Background

In the United States, thyroid cancer has the fastest rising incidence of all the major cancers, accounting for roughly 4% of all new cancer cases. Among the four principal subtypes of thyroid cancer, differentiated papillary and follicular thyroid cancers represent about 90% of cases.

The Treatment Paradigm

At Penn Medicine, as elsewhere, patients with confirmed thyroid cancer traditionally have radical thyroidectomy and central and/or lateral neck lymph node dissection as their first line treatment. Surgery is followed, in some cases, by radioactive iodine (RAI), which is absorbed by and destroys remnant thyroid cancer cells. RAI is the principal therapy for the destruction of malignant cells remaining after primary surgery and contributes to the prevention of recurrent disease.

However, a minority of patients are either refractory to RAI from the outset, develop resistance to iodine uptake over time, or demonstrate an inconsistent response to RAI after previously doing well on the therapy. These RAI-refractory patients were previously beyond the capabilities of traditional treatment.

However, a minority of patients are either refractory to RAI from the outset, develop resistance to iodine uptake over time, or demonstrate an inconsistent response to RAI after previously doing well on the therapy. These RAI-refractory patients were previously beyond the capabilities of traditional treatment.

Among the distinguishing features of the thyroid cancer program at Penn Medicine is a commitment to the disease in its totality, including the RAI-refractory population and other underserved patient populations with difficult-to-treat, complex or resistant disease.

That is what led to the revolutionary development of a new class of therapeutic agents – tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI).

New Treatments for RAI-Refractory differentiated thyroid carcinoma (DTC) at Penn Medicine

Within the Penn Cancer Network, patients with RAI-refractory DTC are referred to the care of renowned clinician researcher Marcia Brose, MD, PhD.

The Penn Thyroid Cancer Therapeutics Program is widely regarded as a pioneer in the field of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapies, a class of drugs that work by hindering the enzymes involved in the proliferation of DTC and other cancers.

The Penn Thyroid Cancer Therapeutics Program is widely regarded as a pioneer in the field of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapies, a class of drugs that work by hindering the enzymes involved in the proliferation of DTC and other cancers.

Dr. Brose was among the first researchers to administer a TKI to a human patient with RAI-refractory DTC in the context of a clinical trial, and was subsequently the principal investigator for DECISION, the national clinical trial of the first FDA approved oral TKI sorafenib in RAI-refractory, locally advanced or metastatic DTC. When sorafenib won FDA approval in 2013 largely as a result of Dr. Brose’s efforts, it became the first effective drug approved for the first-line treatment of RAI-refractory thyroid cancers.

First and Second-Line TKIs for DTC

Since the FDA approval of sorafenib, Dr. Brose has gone on to help develop another TKI, lenvatinib. Both have been shown to be effective as first and second line treatments. The coordination and application of these treatments requires a high degree of understanding of how they function to be optimally effective. All TKIs are susceptible to resistance from kinase pathways that either escape their specific inhibitory activities or evolve the means to evade these processes. This has two implications: first, tolerance will be an issue with each of the TKIs eventually; second, tolerance is manageable as long as another TKI, with another mechanism of action, is available.

As a result, TKIs that work in slightly different ways can be substituted for one another when tolerance takes hold. Because both sorafenib and lenvatinib interfere with the tyrosine kinase pathways in different ways, either can serve as first or second-line therapy.

Because of this concern around tolerance, Dr. Brose began researching a third TKI for RAI-refractory DTC. That drug was the multi-kinase inhibitor cabozantinib, a drug approved for the treatment of medullary thyroid cancer in 2012 following studies contributed, in part, by Dr. Brose.

Dr. Brose is currently leading a global Phase III clinical trial study in 130 sites to investigate the efficacy of cabozantinib as first-line therapy in patient with progressive, RAI-refractory, metastatic or unresectable DTC. The advent of this trial marks the fifth phase 2 study for new therapies in DTC at Penn Medicine.

The Best Hope for Care

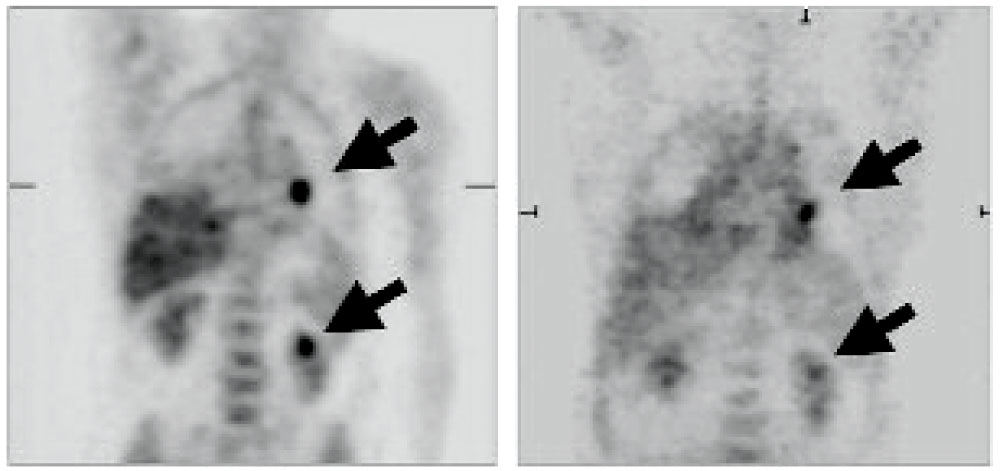

Decreased metabolic activity in two metastatic thyroid lesions in a patient before and after sorafenib treatment

Decreased metabolic activity in two metastatic thyroid lesions in a patient before and after sorafenib treatment

Dr. Brose offers this frank assessment of the scope of the thyroid cancer program at Penn Medicine, and the motivation of its practitioners.

“We treat anyone with complex thyroid cancer,” she says. “Whatever the type or stage of disease, we have a strategy for longitudinal care and the goal of offering these patients every therapeutic option, including investigational and novel therapies.”

Penn Medicine can achieve these goals, Dr. Brose adds, because she and her team have acquired years of experience, and possess a deep and comprehensive understanding of the TKIs. “Our team is unique in our deep understanding of the management of the toxicities associated with these agents which helps us to maximize the clinical benefit while preserving quality of life” Dr. Brose says.

Right now there are only two approved therapies, but here, a patient can stay in one place and have up to four or five lines of therapy due to additional agents available through clinical trials. That’s different from any other academic center.

“Not only are there more options available because we’re pushing the boundaries of what’s available for medical management for these types of patients,” Dr. Brose explains, “but we’re also sequencing them in strategic ways that are influenced by the evidence."